Portraits And Their Diversity

Having experimented now with various genres of photography I find myself being drawn to portrait work, I find the interaction with the subject interesting and enjoyable. I enjoy the diversity of portraiture, the different feels and looks you can achieve. Commercial, fashion, wedding, event and editorial portraiture leaves quite a large field of photography to explore, different lighting set ups, types of lighting, types of diffusers and soft boxes etc...

The Portrait

A photographic portrait is in which the face and its expression is predominant. The

intent is to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the

person. For this reason, in photography a portrait is generally not a snapshot,

but a composed image of a person in a still position. A portrait often shows a

person looking directly at the painter or photographer, in order to most

successfully engage the subject with the viewer.

Portrait photography is a popular commercial industry all

over the world. Many people enjoy having professionally made family portraits

to hang in their homes, or special portraits to commemorate certain events,

such as graduations or weddings. Since the dawn of photography, people have

made portraits. The popularity of the daguerreotype in the middle of the 19th

century was due in large part to the demand for inexpensive portraiture.

Studios sprang up in cities around the world, some cranking out more than 500

plates a day. The style of these early works reflected the technical challenges

associated with 30-second exposure times and the painterly aesthetic of the

time. Subjects were generally seated against plain backgrounds and lit with the

soft light of an overhead window and whatever else could be reflected with

mirrors.

As photographic techniques developed, an intrepid group of

photographers took their talents out of the studio and onto battlefields,

across oceans and into remote wilderness. William Shew's Daguerreotype Saloon,

Roger Fenton's Photographic Van and Mathew Brady's What-is-it? wagon set the

standards for making portraits and other photographs in the field.

Lighting for portraiture

When portrait photographs are composed and captured in a

studio, the photographer has control over the lighting of the composition of

the subject and can adjust direction and intensity of light. There are many

ways to light a subject's face, but there are several common lighting plans

which are easy enough to describe.

Three-point lighting

One of the most basic lighting plans is called three-point

lighting. This plan uses three (and sometimes four) lights to fully model

(bring out details and the three-dimensionality of) the subject's features. The

three main lights used in this light plan are as follows:

Key-Light

Also called a main light, the key light is usually placed to

one side of the subject's face, between 30 and 60 degrees off center and a bit

higher than eye level. The purpose of the Key-Light is to give shape

(modelling) to a subject, typically a face. This relies on the first principle

of lighting, white comes out of a plane and black goes back into a plane. The

depth of shadow created by the Main-Light can be controlled with a Fill-Light.

Fill-in light

In modern photography, the fill-in light is used to control

the contrast in the scene and is nearly always placed above the lens axis and

is a large light source (think of the sky behind your head when taking a

photograph). As the amount of light is less than the key-light (main-light),

the fill acts by lifting the shadows only (particularly relevant in digital

photography where the noise lives in the shadows). It is true to say that light

bounces around a room and fills in the shadows but this does not mean that a

fill-light should be placed opposite a key-light (main-light) and it does not soften

shadows, it lifts them. The relative intensity (ratio) of the Key-light to the

fill-light is most easily discussed in terms of "Stops" difference

(where a Stop is a doubling or halving of the intensity of light). A 2 Stop

reduction in intensity for the Fill-Light would be a typical start point to

maintain dimensionality (modelling) in a portrait (head and shoulder) shot.

Accent-Light

Accent-lights serve the purpose of accentuating a subject.

Typically an Accent-light will separate a subject from a background. Examples

would be a light shining onto a subject's hair to add a rim effect or shining

onto a background to lift the tones of a background. There can be many accent

lights in a shot, another example would be a spotlight on a handbag in a fashion

shot. When used for separation, i.e. a hair-light, the light should not be more

dominant than the main light for general use. Think in terms of a "Kiss of

moonlight", rather than a "Strike of lightning", although there

are no "shoulds" in photography and it is up to the photographer to

decide on the authorship of their shot.

Kicker

A Kicker is a form of Accent-Light. Often used to give a

backlit edge to a subject on the shadow side of the subject.

Butterfly lighting

Butterfly lighting by director Josef von Sternberg is used

to enhance Marlene Dietrich's features, in the iconic shot

From Shanghai Express, Paramount 1932

Photo by Don English

Butterfly lighting uses only two lights. The Key light is

placed directly in front of the subject, often above the camera or slightly to

one side, and a bit higher than is common for a three-point lighting plan. The

second light is a rim light. Often a reflector is placed below the subject's

face to provide fill light and soften shadows.

This lighting can be recognized by the strong light falling

on the forehead, the bridge of the nose and the upper cheeks, and by the

distinct shadow below the nose which often looks rather like a butterfly and

thus provides the name for this lighting plan. Butterfly lighting was a

favourite of famed Hollywood portraitist George Hurrell, which is why this

style of lighting is often called Paramount lighting.

Accessory lights

These lights can be added to basic lighting plans to provide

additional highlights or add background definition.

Background lights

Not so much a part of the portrait lighting plan, but rather

designed to provide illumination for the background behind the subject,

background lights can pick out details in the background, provide a halo effect

by illuminating a portion of a backdrop behind the subject's head, or turn the

background pure white by filling it with light.

Other lighting equipment

Most lights used in modern photography are a flash of some

sort. The lighting for portraiture is typically diffused by bouncing it from

the inside of an umbrella, or by using a soft box. A soft box is a fabric box,

encasing a photo strobe head, one side of which is made of translucent fabric.

This provides a softer lighting for portrait work and is often considered more

appealing than the harsh light often cast by open strobes. Hair and background

lights are usually not diffused. It is more important to control light spillage

to other areas of the subject. Snoots, barn doors and flags or gobos help focus

the lights exactly where the photographer wants them. Background lights are

sometimes used with color gels placed in front of the light to create coloured

backgrounds.

Rembrandt lighting

Rembrandt lighting is a method of studio lighting in which

the subjects face is well lit on one side with only a small triangle of light

appearing on the opposite cheek, such as in the photograph below.

Split Lighting

Split lighting is similar to Rembrandt type of lighting but

even more dramatic. Another term used for this type of lighting is “side

lighting”, used a lot in film noir cinematography. To achieve this look, just

place your main light all the way to the side of your subject. The image will

have one side well lit and the opposite in shadow. Then it’s up to you how much

you want to add detail to the shadows. Just place a second light to the

opposite side of lit area of the subject’s face and adjust the distance.

By placing the fill far away from the subject, you’ll be

able to add just the right amount of the detail. If you place the light too

close, then you’ll end up losing the side lighting effect. You may also add a

background light and aim it to your background. This will help separate the

subject from your background and will give you a three dimensional image.

Broad Light

With this set up you don’t really need to change the

position of your lights much, compared to Rembrandt or split lighting. The

reason it is called “broad light” style, is because the longer side of the

subject’s face is lit. All you need to do is to have your subject face away

from the light, which most of the times is positioned at 45 degrees from the

subject. The subject’s chin, however, will turn to the opposite direction from

the light, therefore the subject’s face from his/her nose to his/her ear will

be well lit. So, is very easy to go from Rembrandt style to broad light style

by just moving the position of the subject.

Also, remember you may have the subject’s face in broad

light style but have the body in Rembrandt style by just having the body face

away from the light. If, on the other hand, the body faces the light, then it

will be broadly lit.

Loop Lighting

The loop light style is just a slight variation from the

Paramount light. All you have to do is move the light to one side, usually to

the right of the camera, but still have it at a high angle. This style, because

of the shadows it creates, gives a sense of depth that other styles don’t have.

The reason is called looped lighting is because of the shadow that is created

under and to the side of the nose that is loop-shaped.

Key Light

The function of the key is to shape the subject. It should

draw attention to the front plane (the “mask”) of the face. Where you place the

key light will determine how the subject is rendered. You can create smoothness

on the subject’s face by placing the light near the camera and close to the

camera/subject axis, or you can emphasize texture and shape by skimming the

light across the subject from the side.

The key light should be a high-intensity light. If using

diffusion, such as an umbrella or softbox, the assembly should be supported on

a sturdy stand or boom arm to prevent it from tipping over. If undiffused, the

key light should have barn doors affixed to control the light and prevent lens

flare.

Here is an example of a really big key light. Charles Maring often uses a 7-foot Profoto reflector as a single key light with no fill. In the close-up of the senior’s eyes (below), you can see the differentiated interior of the round reflector, with varying degrees of reflectivity mirrored in her eyes. A single strobe fired into this reflector created this amazingly soft wraparound lighting. The exposure was at f/16 to keep all the girl’s hair in focus.

In most cases, the key light is placed above and to the side

of the face so that it illuminates both eye sockets and creates a shadow on the

side of the nose. The nose shadow should not cross over onto the cheek, nor

should it go down into the lip area.

When the face is turned for posing, the key light must also

be moved to maintain the lighting pattern. For example, the light will be

positioned at approximately a 45-degree angle to the camera when photographing

the full face of a subject. However, when the subject turns to show the camera

a two-thirds facial view, the key light will need to shift with the camera to

maintain the same lighting pattern as in the first shot.

Normally, you will want to position the main light close to

your subject without it appearing in the frame. A good working distance for

your key light, depending on your room dimensions, is eight to twelve feet.

Sometimes, however, you will not be able to get the skin to “pop,” regardless

of how many slight adjustments you make to the key light. This probably means

that your light is too close to the subject. Move the light back or feather it.

To get an accurate exposure reading, position a handheld

exposure meter directly in front of the subject’s face and point it toward the

light source. Make a few exposures and verify the exposure on the camera’s LCD.

If your system allows you to check a histogram of the exposure, check it to

make sure you have a full range of highlight and shadow detail.

Fill Light.

Just as the key light defines the lighting, the fill light

augments it, controlling the lightness or darkness of the shadows created by

the key light. Because it does not create visible shadows, the fill light is

defined as a secondary light source.

The fill light should always be diffused. If it is equipped

with a simple diffuser, a piece of frosted plastic or acetate in a screen or

frame that mounts over the parabolic reflector, it should also have barn doors

attached. If using a more diffused light source, such as an umbrella or

softbox, be sure that you are not “spilling” light into unwanted areas of the

scene, such as the background. As with all lights, these units can be

feathered, aiming the core of light away from the subject and just using the

edge of the beam of light.

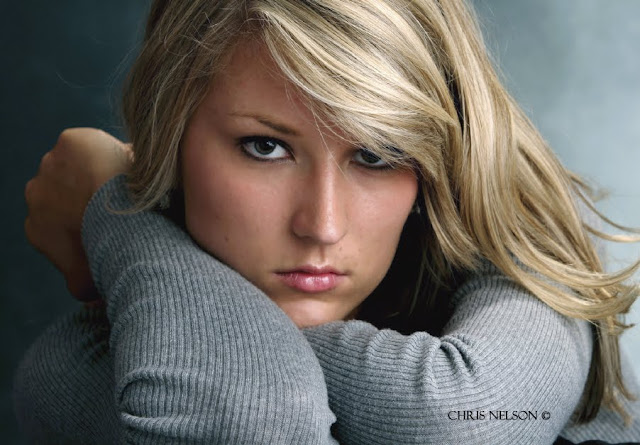

Chris Nelson

photographed this young lady with a softbox as a main light. He used a silvered

reflector for fill, a strip light for the hair light, and a background light.

The softbox and strip light were set to the same output level; the background

light was set to a stop less. The camera angle was about a foot over the

subject using a telephoto lens. He used a fan on low to give her hair some fill

and lift. Chris says of this pose, “Never use it unless your subject has long

sleeves on, and don’t use it if the arms are abnormally large or well

developed.”

The best place for the fill source is as close as possible

to the camera-to-subject axis. All lights, no matter where they are or how big,

create shadows. By placing the fill light as near the camera as possible, all

the shadows that are created by that light are cast behind the subject and are

less visible to the camera.

When placing the fill light, keep a watch out for unwanted

highlights. If the fill light is too close to the subject, it often produces

its own set of specular highlights, which show up in the shadow area of the

face and make the skin appear oily. If this is the case, move the camera and

light back slightly, or move the fill light laterally away from the camera

slightly. You might also try feathering the fill light in toward the camera a

bit. This method of limiting the fill light is preferable to closing down the

barn doors or lowering its intensity.

The fill light can also create multiple catchlights in the

subject’s eyes. These are small specular highlights in the iris. The effect of

two catchlights (one from the key light, one from the fill light) is to give

the subject a vacant stare or directionless gaze. This second set of

catchlights is usually removed in retouching.

In this beautiful

glamour portrait by Tim Schooler, the key light comes from behind the subject a

little to camera right. You can determine this because the right side of her

face and nose are highlighted. The fill light, which is close to the same

intensity as the key light, comes fromcamera left and fills the shadow side of

the model’s face. Additional fill is achieved by the white crepe material,

which is reflecting light everywhere within the scene. You will notice that

even though the lights are fairly even in intensity, the key light still

provides direction and bias.

In simplified lighting patterns, the source of the fill

light may not be a light at all but a reflector that bounces light back onto

the subject. This means of fill-in has become quite popular in all forms of

photography. The reflectors available today are capable of reflecting any

percentage of light back on to the subject, from close to complete reflectance

with various mirrored or Mylar-covered reflectors to a very small percentage of

light with other types. Reflectors can also be adjusted almost infinitely just

by finessing the angle at which they are reflecting the fill light.

Master photographer Drake Buseth often uses the outdoors as

his studio. Even so, a key light and fill light are still called for. Here, a

large softbox was used over the lens as the key light and a large reflector was

angled up from beneath the camera as a fill-in source. The effect produces a

gentle lighting ratio.

THE PERFECT FILL

If it were a perfect world, fill light would be shadowless,

large, and even—encompassing every part of the subject from top to bottom and

left to right. The fill light would be soft and forgiving and variable. And it

would complement any type of key lighting introduced.

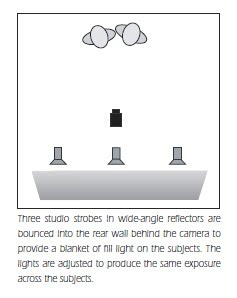

Just such an effect can be created using strobe heads in

wide-angle reflectors bounced into a white or neutral gray wall, or a flat

behind the camera (the surface must be neutral to ensure no color cast is

introduced). Usually, the first two lights are placed to either side of the

camera, then the third is placed over the camera and aimed high off the flat or

the wall/ceiling intersection.

These lights are placed close to the wall and ceiling,

creating a wall of soft light. These fill lights are then balanced to produce

an identical output across the subject. The key light, which may be placed to

the side or above the subject, will be equal to or more intense than the fill

source, creating a ratio between the fill and key lights.

A variation on this setup is to rig a large white flat over

and behind the camera. Two or three strobe heads can then be bounced into the

flat for the same effect as described above. Some of the light is bounced off

the flat and onto the ceiling, providing a very large envelope of soft light.

No comments:

Post a Comment