FIA

My FIA is about my journey into landscape photography and how I aim to deliver that idea into it's final concept and sales. The project will allow me to explore history, my childhood memories and an area long forgotten.

"The Bernica Project" is about a history of our land, a childs memories and an adults passion in landscape photography, turning that passion into sales and a profession.

How did I develop the concept?

The Scottish borders and Northumberland are an inherent part of my own personal history. With a family from Northumberland and many holidays in Scotland and Northumberland as a child it is an area I am familliar with and an area of natural beauty, steeped in history.

The one thing that ties my memories of this area is "Bernica" because Bernica geographically fits my area of exploration.

The History Of Bernica

Bernicia was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian

settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East

England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was approximately

equivalent to the modern English counties of Northumberland and Durham, and the

Scottish counties of Berwickshire and East Lothian, stretching from the Forth

to the Tees. In the early 7th century, it merged with its southern neighbour,

Deira, to form the kingdom of Northumbria and its borders subsequently expanded

considerably.

Situated around modern Durham and Northumberland, the

kingdom was based on one called Bernaccia which seems to have been founded during

the break-up of Romano-British administration in fifth century Britain. A group

of Angles took it over, in AD 547 according to tradition, and pronounced the

existing name as Bernicia.

This group of Angles claimed descent from Benoc's Folk in

Angeln, their homeland in what is now Denmark. They were probably hired and

settled as mercenaries, or laeti, on the north-east coast of Britain in the

very late fifth century, and possibly in the region between the Forth and the

Tyne. It seems possible that they arrived to fulfil the same role as the Jutes

originally had in Kent, to help defend the borders against devastating Pictish

and Scotti raids. The fact that it seems to have taken them so long to mount a

takeover bid probably speaks volumes of the readiness of the Northern British

to defend their territory.

While the Angles seemed to have taken over with very little

fuss, during a power gap, according to later tradition the former British ruler

continued to fight on from outside his former lands until at least 590. It also

seems possible that the Bernician Angles had a hand in founding neighbouring

Deira as an independent kingdom, as tradition and King Ida's date of death

indicate fighting against the British kingdom of Ebrauc was undertaken. Nennius

(whatever his unreliability) seems to back this up in 550 and 561.

Bernician royal residences were at Bamborough and Yeavering

(known originally as Ad-gefrin, no doubt from the Brythonic 'hill of goats').

An impressive assembly of wooden structures has been excavated there.

For three and a half centuries Britain was under Roman rule.

The Romans built roads, towns, forts and temples, bringing with them soldiers

and cultures from across Europe. They conquered the native 'Celtic' tribes of Britain

and established military control in the North with the construction of

Hadrian's Wall and the huge legionary fortress at York. In the reign of

Constantine the Great, they also brought Christianity. Constantine, who was

proclaimed Emperor at no less a place than York, would himself become the first

Emperor to convert to Christianity.

By 314 York was one of a number of important places in the

Roman empire with a Christian bishop. Christianity was however, only one of a

number of religions accepted within the Roman empire and it is not known how

many Britons were actually Christians. The native people of Britain were

ancient Britons, speaking a Celtic language resembling Welsh, but of course

many would also learn to speak the Latin of the Romans. Many of these people

continued to practice their native Celtic 'pagan' religions, while others may

have adopted more exotic religions introduced from other parts of the Roman

empire. One thing is certain however, in 300 years of occupation the Britons

had intermixed with the multicultural Romans to form a 'Romano-British'

society, quite different from the Celtic culture of pre-Roman times.

In the vicinity of Roman forts, native Britons intermarried

with Roman soldiers enlisted from far flung corners of the Roman empire like

Iraq or North Africa. At Housesteads on the Roman Wall, they may even have

intermarried with members of the Roman garrison of Anglo-Saxon soldiers

stationed at that particular fort. But we should remember that these

Anglo-Saxons were not yet native to our shores and originated from the Germanic

lands of the continent.

By 399 AD, three and half centuries of Roman rule in Britain

were drawing to an end as the Romans commenced the removal of their troops from

Britain. Attacks on Rome by the Visigoths from eastern Europe meant that

reinforcements were desperately needed elsewhere and the Romans could no longer

hold on to Britain as a military province. In the North of Britain, the

depletion of the Roman army left the northern frontier of Hadrian's Wall

severely exposed and revolts against the small scattering of Romans who

remained soon gained momentum.

ANGLO-SAXONS

Virtually all Roman troops had departed from Britain by 410

AD, leaving our shores and internal borders defenceless. The north was particularly

vulnerable to attack, not just from Picts and Scots in the north, but from

Anglo-Saxon raiders from across the North Sea. These Germanic raiders consisted

of two main groups, the Angles (or Anglians) from what is now the border of

Germany and Denmark (Schleswig Hosltein) and the Saxons from what is now

Northern Germany.

During the later centuries of Roman occupation, the Romans

had built several defensive watch towers along the coast to defend against the

Anglo-Saxon raiders. In the north, examples could be found at Scarborough,

Goldsborough, Filey and Saltburn, but there were almost certainly others. When

Roman rule came to an end the Anglo-Saxons no doubt continued to raid the coast

but some found themselves employed by the native Britions as mercenaries to

defend Britain against the Scots and Picts. Many Anglo-Saxons were given land

in Britain as a return for their protection, but it became increasingly

apparent to the new settlers, that Britain was now a vulnerable province that

was there for the taking.

The Angles had begun to invade and settle all parts our

eastern shores, seizing the region they called East Anglia by 440, along with

Lincolnshire and regions further inland. It is likely that the North East was

already under attack or at least bracing itself for invasion, but some aspects

of the Roman way of life still persisted. It is known, for example, that in 445

AD, Newcastle upon Tyne was still known by its Roman name of Pons Aelius - the

site of a fort adjoining a bridge over the Tyne.

EARLY SETTLEMENTS

By 450 AD, the Angles had begun their invasion of the north,

colonising land in the Yorkshire Wolds, just to the north of the Humber in a

land they called Deira. This name was probably an adapatation of an exisiting

Celtic tribal region or kingdom. Gradually the Angles would invade territory

further north and began settling the lowland river valleys of the east coast

including possibly the Tyne, Wear and Tees. Excavations at Norton on Teesside,

have revealed evidence of Anglo-Saxon settlement in this early period. It is

also possible that one group of Angles from Lincolnshire - a region then known

as Lindis feorna (later Lindsey) colonised and named the island we know today

as Lindisfarne. Lindisfarne was certainly known in early times as Lindis feorna.

Much further south on the southern shores of Britain, the

Saxons were settling and establishing new kingdoms like Essex, Sussex and

Wessex, whilst a similar Germanic people called the Jutes were colonising Kent

and the Isle of Wight. There was of course native British resistance to their

attacks, but it is recorded that the Britons were heavily defeated by the

Anglo-Saxon invaders at a Battle located at some identified spot called Mons

Badonicus.

The early Anglo-Saxon period was undoubtedly an age of war

and turmoil and our knowledge of this period is scanty. It is this early age of

Anglo-Saxon invasion that is often associated with King Arthur, a Briton who is

said to have fought against the Anglo-Saxons. He is reputed to have died in

537, perhaps on the Roman Wall, but little can be said of Arthur, since so

little is known. He may not have existed at all. To give too much attention to

a shadowy figure like Arthur, himself largely a creation of later Medieval

writers would give a distorted and unreliable view of Anglo-Saxon history. It

is largely the stuff of fiction and can cast doubt, quite wrongly, on the whole

Anglo-Saxon period that follows. The so called 'Age of Arthur' is one period of

British history about which we know very, very little and yet so much has been

written, perhaps because it stretches the imaginations of writers.

Our limited knowledge of this early period has led to the

term 'Dark Ages' but it would be quite wrong to apply this term to the whole

Anglo-Saxon age, since the Anglo-Saxon era is in fact a period about which we

know a great deal. However, in the earliest period of Anglo-Saxon history it is

very much a case of history's gradual emergence from darkness.

One important clue to the early settlement of Anglo-Saxons

is in place names, as most of the place names of our region and indeed of

England as a whole, are of Anglo-Saxon origin and often tell us the names and

activities of the first Anglo-Saxon settlers. Significantly, almost all places

ending in 'ton' or 'ham' are of Anglo-Saxon origin, but there are many other

types of Anglo-Saxon place names. Interstingly the original Celtic and

Romano-Celtic places names are very rare in England.

We know, that before the Anglo-Saxons arrived, the North

East, like the rest of Britain was occupied by the descendants of the Romanised

Celts and earlier peoples. In the far north, one group of these Celtic people

had developed into a tribal kingdom called the Goddodin in the Lothians with

their tribal fort and capital located at Din Eidyn (Edinburgh). The Goddodin

are thought to have been the descendants of the Votadini, a tribe that

inhabited this territory along with Northumberland in the early days of the

Roman invasion. In 538 AD the Gododdin were not yet under siege from the

Anglo-Saxons but they were defeated in a great battle at Edinburgh after an

onslaught by the Caledonians, a massive confederation of highland tribes from

northern Scotland.

BERNICIA AND DEIRA

The most important date in this otherwise dark period of

nortern history was 547 AD. In this year, the ancient British coastal

stronghold of Din Guyaroi (Bamburgh) on the North East coast was seized by the

Angle chief called Ida the Flamebearer. His seizure of this important British

stronghold was an important event in the Angles' political and military seizure

of the North. It is is a year often regarded as the first real date in the

history of the kingdom that would come to be known as Northumbria. It is likely

that Ida already had a foothold in the Tyne, Wear and Tees region, but the

populous native British lands in the vicinity of Din Guyardi were an important

addition to Ida's expanding Kingdom of Bernicia. The name of this emerging

kingdom, was like Deira, probably an adaptation of an existing Celtic name and

would come to be synonymous with the North Eastern region in the centuries to

come.

Ida had conquered huge areas of land in the North East by

550 including some territory south of the Tees. He was now undisputedly the

most powerful leader in the northern Angle Land (later England) and Din Guyardi

or Bamburgh was the capital of his kingdom. In 560 he was succeeded by his son

Theodoric, whose domain was confined to Bernicia, north of the Tees, but some

of the remaining Celtic kingdoms that existed in the north, saw him as a weaker

leader than his father and refused to accept his rule.

Meanwhile, in the Yorkshire Wolds (known to the Angles as

Deira) an Anglian chief called Aelle was rising to power and conducting his

people against the native Britons. Aelle can be regarded as the first king of

Deira. Rivalry between Deira and Bernicia would be a long running feature of

Anglo-Saxon history in the north. However, the native Celts were not yet completely

subdued. Urien, the leader of the British kingdom of Rheged (based in Cumbria)

was determined to fight for the Celtic cause. In 575 AD, he besieged King

Theodoric of Bernicia on the island of Lindisfarne in a siege that lasted three

days, but victory could not be claimed.

The island of Lindisfarne, in close proximity to the

Bernician capital of Bamburgh seems to have been an important location in the

early battles between Britons and Angles in the North. Little is known of this

period but it was on Lindisfarne in 590 AD that Urien of Rheged would meet his

end fighting against the Anglo-Saxons. It is thought that he was betrayed by

Morgan, a leader of the Goddodin tribe from north of the Tweed.

KING AETHELFRITH

In 593, Aethelfrith, the grandson of Ida the Flamebearer,

became the new King of Bernicia in the North-East of England. Without a

formidable, like Urien, his power seemed assured even in the Celtic regions. In

598 Aethelfrith's men heavily defeated the native Britons in a great battle at

Catterick. Here was located the ancient British kingdom called Catraeth centred

on the Tees and Swale. The battle was the result of a major campaign and a huge

army of Britons had marched there after assembling at Edinburgh. The Britons

included the people of Gododdin, Rheged and Northern Wales. It was as if the

Britons were engaging in a last stand against the Anglo-Saxons. But they were

heavily defeated by Aethelfrith. The kingdom of Catraeth was seized.

Aethelfrith's power was now beyond dispute and the Celts

were forced to accept his rule. That is not to say that large areas of the

north instantly became Anglo-Saxon. The settlement of Anglo-Saxons was

extensive, but Celts were still predominant in Cumbria, the Pennines, the

Celtic Kingdoms of Loidis (Leeds), Elmet and Meicen (in Hatfield, the marshy

country near Doncaster).

In 603 Aethelfrith turned his attention to the Celts of the

far north, going into battle with Aidan MacGabrain, King of the Dalriada Scots.

The Dalriada Scots lived in western Caledonia but originated from Hibernia

(Ireland). During the battle, the Scots were assisted by a large force of

Ulstermen, but were defeated in battle at Degastan, an unknown location,

possibly in Liddesdale. Aethelfrith's victory forced the Kingdoms of

Strathclyde in the west, Rheged in Cumbria and Gododdin in the Lothians to

recognise Bernician superiority once again. With his power and prestige assured

Aethelfrith usurped the crown of Deira in Yorkshire. He thus became King of

both Deira and Bernicia, uniting all the Angle territory north of the River

Humber into one kingdom called Northumbria. Bernicia and Deira were reduced to

mere sub kingdoms.

Of course there were many in Deira who disliked Bernician

rule, so Aethelfrith encouraged Deiran support by marrying Acha, a member of

the Deiran royal family. It was unlikely to stop Acha's brother Edwin from

claiming the kingdom of Deira but it was too dangerous for Edwin to remain in

Northumbria and he sought protection at the court of King Cearl of Mercia (an

Angle kingdom based in the Midlands). Edwin's presence in Mercia was a constant

threat to Aethelfrith.

In 615, the Bernician capital Din Guyardi, was renamed

Bebbanburgh in honour of Bebba, Aethelfrith's new wife. The name meant the fort

of Bebba, but it would gradually come to be pronounced Bamburgh. This was

perhaps one of many Celtic place names that were replaced by Anglo-Saxon names

in this period and may reflect the gradual replacement of Celtic with

Anglo-Saxon speech. It seemed that the native Celts were no longer the major

threat to the expansion of the Angles and Aethelfrith for one was now

preoccupied with defeating his Anglian rival.

Later in 615 AD, he ousted King Cearl from the Kingdom of

Mercia and took virtual control of the midland kingdom, although he employed a

Mercian to look after Northumbrian interests here. Edwin, Aethefrith's major

Northumbria rival fled from Mercia and took refuge with the King of East

Anglia. Edwin was still a threat to Aethelfrith, but a seemingly more distant

one and it seemed there would be no end to Aethelfrith's expansion. In 615,

Aethelfrith defeated the Welsh in battle at Chester and once again seized

Cumbria, bringing it firmly under Northumbria rule. It was a significant event

as it isolated the Britons of North Wales from those of Strathclyde and the

Lothians, although that is not to say that the Britons were exterminated in the

District of the Lakes.

However, Aethelfrith's expansion would not remain unchecked

forever. In 616 he finally met his end in battle against Raedwald King of East

Anglia at Bawtry on the River Idle. This site lies close to the present borders

of Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire. In Aethelfrith's time this area

lay on the southern reaches of Northumbria, a dangerous marshy region close to

the border with Lindsey and easily accessible from the East Anglian kingdom.

KING EDWIN

Upon Aethelfrith's death, Edwin, son of Aelle and prince of

Deira seized the Northumbrian kingdom. A Deiran was now in charge of the

Northumbrian kingdom, but there was still rivalry between Deiran and Bernician

factions. The Bernician claimant was Aethelfrith's son Prince Oswald, who fled

from Northumbria for safety. Oswald took refuge on the island monastery of Iona

off the western Scottish coast. Political expansion and victory in battle was a

necessary part of being an Anglo-Saxon king if he wished to gain support and

respect and this was as true for Edwin as it had beeen for Aethelfrith.

Much of Edwin's early military activity seems to have

concentrated on the southern borders of Northumbria where there was still

strong Celtic influence. Around 626 he evicted a client king called Ceretic

from the ancient British kingdom of Elmet near Leeds and followed this with the

capture of the Celtic kingdom of Meicen (Hatfield) near Doncaster. His

expansion also extended south into the Angliankingdom of Lindsey

(Lincolnshire).

Since Edwin already had control over much of the land

acquired by Aethelfrith, Edwin's power in the north was unequalled by any

Anglian predecessor. But power and expansion naturally aroused jealousy and

fear amongst rivals including Cuichelm, King of the West Saxons. In 626

Cuichelm sent north an assassin called Eumer, who attempted to kill Edwin as he

celebrated the Pagan festival of Easter at his royal palace somewhere close to

the River Derwent on the edge of the Yorkshire wolds. The assassin entered the

King's court and asked to speak with the king on the pretence of having an

important message from the West Saxon King. On seeing the king, Eumer produced

a poisoned dagger from beneath his cloak with which he attempted to stab Edwin.

Fortunately one of Edwin's men, Lillam jumped in the way and suffered a blow

from which he was killed. A fight followed in which Edwin was injured but Eumer

was eventually put to death. On the same night of the assasination attempt King

Edwin's queen, Ethelburga gave birth. Angered by the assasination attempt,

Edwin sought revenge and defeated the West Saxons in a great battle in Wessex.

As a result Edwin proclaimed himself 'overking' of all England.

EDWIN'S CONVERSION TO CHRISTIANITY

Until this point, all the Northumbrian kings, including

Edwin, had been solidly Pagan in their outlook, but this was about to change.

Edwin had already formed an important alliance with the Kingdom of Kent, an

Anglo-Saxon Kingdom that had converted to Christianity through the influence of

St Augustine. In 625 a marriage had been arranged between Edwin and the

Christian Princess of Kent called Ethelberga. Edwin was already considering his

own conversion to Christianity and Edwin took the opportunity to attribute his

victory in Wessex to the new Christian faith.

On April 11 627, Edwin converted to Christianity,

undertaking a baptism at York performed by a Roman missionary called Paulinus.

The ceremony took place in a new, wooden church dedicated to St Peter. This

humble little building was the predecessor of York Minster. Coifi, the Pagan

high priest under Edwin, followed the king's example and he too converted to

Christianity. To demonstrate his new faith Coifi destroyed the great heathen

temple of Goodmanham near the River Derwent in East Yorkshire.

Paulinus was appointed as Bishop of York, a post redundant

since Roman times. He travelled throughout Northumbria converting Edwin's

people at important locations associated with the Royal household. He is said

to have baptised thousands of Northumbrians in the Swale near Catterick and in

the River Glen near Yeavering.

At Yeavering the outline of one Edwin's Royal Palaces can

still be seen in the fields. It is only visible from the air but includes the

clear outline of several buildings including a great hall and an auditorium. It

is thought that Northumbrians assembled here to hear the words of influential

speakers. Perhaps Edwin and Paulinus addressed an audience on this spot.

Interestingly the palace lies at the foot of a prominent hill called Yeavering

Bell, itself the site of a large Celtic fort. Was this perhaps one of many

locations where Celtic and Anglian cultures merged together. Perhaps some of the

Celtic peoples of the region had even held onto Christian beliefs since Roman

times and it is just possible that in some cases Paulinus was preaching to the

converted.

It is very tempting to look for the continuous presence of

Christianity in England since Roman times. It may be significant that York, so

closely associated with the great Christian Emperor Constantine and the site of

a Roman bishopric was chosen by Edwin as the centre for his Christian activity.

The new wooden minster built by Edwin at York lay within what had been the

headquarters building of the Roman legionary fortress. In 628 AD Edwin rebuilt

the church of St Peter's in stone and he may have used rubble from the Roman

fortess in its construction. Anglo-Saxon churches certainly made use of Roman

stone as is demonstrated by the Anglo-Saxon church at Escomb in County Durham.

Of course it is also known for certain, that the very name of the minster at

York - its dedication to St Peter - was chosen to reflect its links with St

Peter's in Rome. The church was given sealed approval by the Pope.

It would be wrong, however, to assume that Roman

Christianity was now firmly re-established in the north. Its future was only

assured as long as Edwin remained in power. On October 12, 633, Edwin was killed.

As with Aethelfrith, Edwin's death took place in a battle within the marshy low

country near Doncaster. On this occasion the battle was at Heathfield (or

Hatfield) where Edwin's forces were crushed by the Mercians in alliance with

the Welsh. The Mercians fought under the leadership of a chieftain called Penda

and the Welsh assisted under the their king Caedwalla. Osric, a possible

successor to Edwin was also killed in the battle whilst Edwin's son Edfrith

surrendered.

Penda was appointed King of the Mercians and along with his

Welsh ally Caedwalla could now claim to be one of the most powerful kings in

the north. Caedwalla had his eye on Northumbrian territory and claimed the

throne of Deira. It may sound sound strange that a Welshman would claim Anglian

territory in Yorkshire, but many parts of this region will have still

encompassed Welsh speaking territory and peoples particularly in the Pennines

and in the former Celtic kingdoms near Leeds and Doncaster.

So what was the future for Christianity in the North? In

Bernicia, Eanfrith, the pagan son of Aethelfrith was crowned King of the

Northumbrians and those who had converted to Christianity during Edwin's reign

may have thought it wise to revert to Eanfrith's Pagan ways. St Paulinus, the

Christian Bishop of York returned to Kent.

KING OSWALD

There was still hope for the Christian cause. In 634

Eanfrith was killed by his younger brother Oswald, who had returned from his

exile on the Christian island of Iona. Oswald became King. The following year

Oswald heavily defeated Penda and Caedwalla in battle at Heavenfield just to

the south of Hexham. The event resulted in Caedwalla's death. Oswald's victory

over Penda at the Battle of Heavenfield made him the undisputed overking (or

Bretwalda) of England. This was a title that had also been held by Edwin, but

was more of a recognised status of 'top king' than an absolute king of all

England. Oswald attributed his victory at Heavenfield to the work of God. As an

expriment he had asked his men to pray to God prior to the battle and was now

convinced that the Christian faith had brought him victory.

Oswald was determined to continue the reintroduction of

Christianity to the North East and employed St Aidan, an Irish monk from the

Scottish island of Iona to convert his people. This would, however, be a Celtic

Christianity, different to the Roman style of Christianity introduced by Edwin

and Paulinus. Aidan, perhaps trying to recreate the atmosphere of Iona, chose

Lindisfarne as the centre for his bishopric and established a monastery on the

island. He was the first Bishop of Lindisfarne.

Other monasteries would follow and in 640 a monastery was

established on the coastal headland at Hartlepool by Hieu an Irish princess who

became the first abbess there. Like Lindisfarne this too, had an island like

location, as the Hartlepool headland was virtually cut off from the mainland.

Further south York's Christian credentials were not forgotten and in 642 AD

Oswald completed the work begun by King Edwin on St Peter's Minster church.

Also in Yorkshire Lastingham Priory established in 654 by St Cedd.

One lesser known monastic site of the period was Gateshead.

This was known to the Anglo-Saxons as 'Goat's Head' as translated from Bede's

Latin name for the site 'Ad Caprae Caput'. Little is known about the monastery

her except that it was under the jurisdiction of an abbot called Uttan in 653.

The name Goat's Head may have been taken from some kind of totem or emblem,

perhaps of Roman origin, that may have existed on the Roman Tyne Bridge.

Christianity did not of course bring an end to Northumbria's

political expansion. In 638, the Lothian region was besieged by Oswald who

brought it under Northumbrian control. Din Eidyn, once the chief fortress of

the Gododdin, was brought under Northumbrian control and it was the

Northumbrians that gave the fortress its Anglian name 'Edinburgh', perhaps in

an attempt to associate it with king Edwin. The 'burgh' in Edinburgh is

certainly an Anglian word and means 'stronghold'. Extensive

Northumbrian-Anglian settlement must have taken place here since most of the

place names in this region are still Anglo-Saxon to this day. Interestingly the

form of English spoken in Scotland would also develop from the

Northumbria-Angle speech introduced to the Lothians rather than the earlier

Welsh-Celtic type of language spoken by the Gododdin or the Gaelic type of

Celtic language spoken by the Scots.

There was to be no peaceful break from military conflict in

the North and it seemed certain that Oswald would eventually, like his

predecessors, lose his life on the battlefield. And so it was on August 5, 642

AD, Oswald, King of Northumbria died in battle at Maserfelth against Penda of

Mercia. The location of the battle is uncertain, with the two main suggestions

being Makerfield in Lancashire or Oswestry in Shropshire.

KING OSWY

Oswald was succeeded by his brother Oswy in Bernicia (the

North East region north of the Tees) and by a rival called Oswine in Deira

(Yorkshire). This meant that Northumbria was split into two parts once again.

The split weakened the kingdom and Penda of Mercia took the opportunity to

seize certain Northumbrian lands in Deira, Lincolnshire and Elmet near Leeds.

Oswine of Deira was now under threat from all sides and was eventually murdered

after backing down from military confrontation with Oswy at Wilfar's Hill near

Catterick. Oswine's hiding place at Gilling was discovered by one of Oswy's

men.

So Oswy seized the Deiran crown, making his claim on the

strength of his marriage to Eanfled, daughter of the late King Edwin. So

Northumbria was once again united. Ethelwald, the son of the late King Oswald

was employed by Oswy to take care of the king's affairs in Deira, but he

betrayed Oswy, siding with Penda of Mercia in an attack in 653. This attack

that took the raiders as far north as Bamburgh.

War raged between Mercia and Northumbria and on November 15,

655, the Mercians and Welsh were defeated in a great battle. Its location is

not certain, but the battle is described as being near the River Winwaed. The

river is unidentified so its name must have changed at some later point in

time, but it is generally agreed that it was somehwere near Leeds. It was a

very important battle since Penda, the King of Mercia and thirty enemy

chieftains were killed. Many of the Mercians were drowned in the river as they

tried to escape.

Oswy's victory placed him in a position of great prominence

in England. Not only was he now the undisputed King of Northumbria but he was

also proclaimed 'Bretwalda' - the 'top king' of all England. Oswy's control of

Deira was assured but now he also had a say in Mercian affairs, appointing

Penda's son Peada (after whom Peterborough is named) as King of Mercia south of

the Trent. Oswy seized northern Mercia for himself.

SAINT WILFRID

The defeat and death of King Penda of Mercia at the Battle

of Winwaed in 655 seemed to mark the beginning of a new period of Northumbrian

greatness. It was certainly an age of important Christian developments in the

region. The establishment of new monasteries continued, such as that at Ripon

founded in 657 by Irish monks from Melrose. At around the same time St Hilda,

abbess of Hartlepool founded a monastery at Streanashalch (Whitby).

This was also a period of great debate about the kind of

Christianity that should be practised in the North. In the reign of Edwin,

Roman Christianity had been introduced to the North, but during Oswald's reign

a Celtic form of Christianity was preferred. This meant that Northumbria was

out of touch with the rest of England and Europe.

In the year 664 a great synod was held at Whitby to discuss

the controversy regarding the timing of the Easter festival. Much dispute had

arisen between the practices of the Celtic church in Northumbria and the

beliefs of the Roman church. The main supporters of the Celtic Christianity at

Whitby were Colman of Lindisfarne, Hilda of Whitby and Cedd, the Bishop of

Essex. St Wilfrid, a well travelled man championed the Roman Christian cause

and successfully persuaded the Northumbrians to reject their old ways.

Colman, the Bishop of Lindisfarne resigned and returned to

Iona and was replaced by Bishop Tuda, the first Bishop of Lindisfarne to

practice the Roman ways. Tuda's reign as bishop was short lived and later in

the year he died of plague. Wilfrid was chosen as his successor and although

Wilfrid agreed to take up the post, he transferred the bishopric from

Lindisfarne to York, perhaps to distance himself from the Christian Celtic

traditions of the Northumbrian island.

Wilfrid was keen to prove a point with a staunch adherence

to the strict rules of the Roman church. He claimed that there was no person in

England who could consecrate him as bishop and so headed off to France to be

ordained. This infuriated King Oswy who replaced the absent bishop with St Chad

of Lastingham.

KING ECGFRITH

King Oswy died in 669 and was succeeded by his son Ecgfrith

who allowed St. Wilfrid to return to England and take up the post of Bishop of

York. Wilfrid established a grammar school at St Peters in York and commenced

the building of a new minster in the city. He also established a new monastery

at Ripon.

In the background to these Christian developments

Northumbrian military and political expansion continued and by 672 the Celts of

Cumbria and Dumfries were conquered by the Northumbrians under Ecgfrith's

leadership, whilst the Picts of Caledonia were defeated in battle. In the

following year Ecgfrith would also defeat the Mercians (Midlanders) in battle.

Northumbrian supremacy was once again confirmed, but Ecgfrith was soon to find

himself involved in conflict away from the battlefield. In 673 he divorced his

virgin queen Ethelreda of Ely in order to marry his new love Ermenburga. The

chaste Ethelreda, under the influence of St. Wilfrid, chose to become a nun and

was given land at Hexham by her former husband. Ethelreda chose to give her new

land to Wilfrid for the building of a monastery. She herself opted for the

coast and established a new monastery at St Abbs Head (north of Berwick).

The year 674 saw the establishment of what would become one

of the most important Roman Christian monasteries in the north. The monastery

of St Peters, Monkwearmouth was founded by a noble called Benedict Biscop on

land granted by King Ecgfrith. A great library would develop here, with books

from France and Rome and the first coloured glass in England would be

introduced to the monastery by continental glaziers. Gregorian chanting was

introduced and many other advanced aspects of Christian culture hitherto

unknown in the north came to Monkwearmouth under Biscop's influence.

Meanwhile tensions between King Ecgfrith and Wilfrid continued

to rise and in 678 the king banished Wilfrid from Northumbria. It is possible

that Ecgfrith may have been jealous of Wilfrid's long standing friendship with

his former wife, now a nun at St Abbs Head. The king broke up Wilfrid's York

based bishopric into two parts with two separate sees centred on York and

Hexham. The bishopric of Hexham extended from the River Tweed to the River Tees

whilst that of York extended from the Tees to the Humber.

Wilfrid, in exile in Europe, turned his attention to the

conversion of the Frisian people of North West Germany. He would return to

Northumbria in 680 but was arrested after landing at Dunbar. Wilfrid had

brought with him papal documents overthrowing the division of the Northumbrian

bishoprics, but the king of Northumbria would not take orders from the Pope and

Wilfrid was imprisoned. He was later released and fled to Sussex where he

converetd the last pagan kingdom in England to Christianity. Wilfrid claimed

that King Ecgfrith had no right to divide the Northumbrian bishopric, but the

king was unmoved by the papal orders. In fact, in the year 681 Ecgfrith made a

further division dividing the new Bishopric of Hexham into two parts with the

re-establishment of a separate bishopric at Lindisfarne. Hexham's diocese would

now extend from the River Aln to the River Tees.

With his control over the church firmly recognised, King

Ecgfrith turned his attention once more to military matters and for the first

time attempted to take Northumbrian expansion overseas by sending an army into

Meath in Northern Ireland in 684. He may have hoped to expand his empire into

these new lands but nothing seems to have developed from this particular

campaign. One person who had advised the king against this particular campaign

was St Cuthbert. In his younger days Cuthbert, had become a popular and well

respected figure noted, apparently, for his gift of working miracles and

healing the sick.

Cuthbert had retreated to the island of Inner Farne in 676

to live as a hermit - once a common practice among those who wished to be

closer to God. Despite his hermit lifestyle, Cuthbert was visited by many, many

people in search of healing. The respect he commanded amongst the people made

him an ideal choice for a bishop. In 685 he was elected as the Bishop of Hexham

at a synod near Alnmouth, but he requested a transfer to Lindisfarne. Cuthbert

was consecrated Bishop of Lindisfarne at York on April 7th in the presence of

King Ecgfrith.

KING ALDFRITH

On May 20 685, King Ecgfrith of Northumbria was killed

fighting Brude, King of Caledonia. It symbolised an end to the period of

Northumbrian expansion. One result of the defeat was the abandonment of yet

another Northumbrian bishopric at Abercorn near Edinburgh. Aldfrith the

illegitimate son of the late King Oswy and an Irish princess, became the new

King of Northumbria and although his reign seemed to signify and end to

political expansion, art and learning would flourish under his rule. Great

works of Celtic art would be encouraged by the new King who had been educated

in Ireland.

The year in which Aldfrith succeeded as king, saw Benedict

Biscop's completion of the monastery of St Pauls at Jarrow, a twin monastery to

Monkwearmouth. Among the new students at Jarrow was Bede, a young boy of nine

years old, who had been transferred from Wearmouth to the new site.

Unfortunately plague hit the two monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow in 686,

while their founder Benedict Biscop was in Rome. Fortunately Bede and the Abbot

Ceolfrith of Jarrow were among the few survivors of the plague.

On March 30, 686 St Cuthbert, perhaps sensing his time was

nearing an end, resigned from the post of Bishop of Lindisfarne and returned to

the island of Inner Farne as a hermit. Later that year Cuthbert died on his

lonely island with only sea birds and seals for company. Northumbria mourned

the loss of its best loved saints. St Wilfrid returned to Northumbria in that

year to become Bishop of Lindisfarne but within two years had transferred to

Hexham. He succeeded St. John of Beverley who retired to become a hermit.

Eadbert replaced Wilfrid at Lindisfarne.

Only four years passed before St Wilfrid found himself once

more at the centre of contoversy. Once again the issue was over the creation of

a bishopric with Wilfrid refusing to allow the creation of a new bishopric

based at Ripon. Wilfrid was banished from Northumbria and John of Beverley was

reinstated as Bishop of Hexham. Wilfrid turned his attentions to Mercia where

he founded at least six monasteries in the period 691 to 703, but his influence

was being felt further affield. In November 695, a Northumbrian monk called

Willibrord, a former pupil of Wilfrid at Ripon, was consecrated Bishop of the

Frisians. Wilfrid's fortunes in Northumbria would improvd on December 4, 705

when Aldfrith King of Northumbria died at Driffield in the Yorkshire Wolds.

BEDE AND THE GOLDEN AGE

Weak leadership was beginning to characterise Northumbrian

affairs, but the church was growing from stength to stength and no religious

house was perhaps more influential than the joint monastery of

Wearmouth-Jarrow. On January 12, 690 Benedict Biscop, the founder of

Monkwearmouth and Jarrow monasteries died of palsy. He was succeeded by

Ceolfrith who became abbot of both monasteries. Two years later in 692 Bede, a

sholar at Jarrow monastery was ordained as a deacon at the age of nineteen. By

703 Bede progressed to the rank of priest.

Bede was something of a star pupil and was fortunate enough

to be growing up in one of the most influential and learned monasteries in

Europe. The monks of this monastery were well travelled and their opinions were

respected. In 716 Ceolfrith, the Abbot persuaded the island monastery of Iona

in Caledonia to abandon its Celtic Christian ways in favour of the Roman style

of Christianity. Ceolfrith's successor continued this work persuading Nechtan,

the King of the Picts to convert to Roman Christianty.

This was an era of great art and literature, which saw the

publication of an illuminated bible called the Codex Amiatinus at Jarrow and

the completion of the beautiful Lindisfarne Gospels at Lindisfarne in 721. At

Jarrow, Bede was writing the Life of St Cuthbert, a work specially written for

the monks of Lindisfarne, but there were other works for which he would achieve

greater fame. A chronolgical work published by Bede in 725 introduced dating

from Christ's birth - Anno Domini and this was eventually adopted by the entire

Christian world. He did not invent the concept of AD but it is widely due to

him that this system of dating was so widely adopted.

But Bede's greatest work was undoubtedly his History of the

English Church and People completed in the year 731 at Jarrow. He dedicated

this work to King Ceolwulf of Northumbria. It was to become one of the most

important sources of information about the history of the Anglo-Saxon period

and was undoubtedly the first history of England ever to be written. Bede was

one of the most respected figures of his day and such was his influence that

his presence in Northumbria helped to persuade the pope to upgrade the

Bishopric of York to the status of an Archbishopric in 734. The first Archbishop,

Egbert, a former pupil of Bede would now be independent of Canterbury.

When Bede passed away at Jarrow on May 25, 735 Northumbria

would mourn the loss of its greatest scholar and historian. His name would be

remembered in history for centuries to come. He was the greatest man of

learning of the Anglo-Saxon age and his works would be known throughout Europe.

The joint monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow were the brightest lights of

learning in 'Dark Age' Europe. The age of Bede was something of a heyday for

the Kingdom of Northumbria, but in the late eighth century Northumbria was

plagued with weak leadership and collapsed into a state of anarchy caused by

rivalry between the royal houses of Deira and Bernicia.

WEAKER KINGS

King Aldfrith of Northumbria, who died in 705 was succeeded

by his son Osred who was only a boy. The boy king was besieged at Bamburgh, but

his attacker Eardulph was captured and beheaded. St. Wilfrid soon emerged as

the young king's protector and adopted faher and was reinstated as Bishop of

Hexham after a synod was held near the River Nidd in North Yorkshire. But

Wilfrid was now well into old age and in the year 709, he died while visiting

his Mercian monastery at Oundle, Northamptonshire.

Wilfrid was succeeded by Acca as the new Bishop of Hexham

and received burial at Ripon. Remarkably, Osred the boy king held on to power

in the north and in 711 the Northumbrians even managed to defeat the Picts in

battle, preventing the expansion of the Pictish kingdom. That this was a

campaign of defense is perhaps telling, the days of Northumbrian expansion were

now over and as the decades passed the history of the kingdom would be plagued

by infighting.

In 716 Osred, was assasinated at the age of nineteen, near

the southern borders of his kingdom by his kinsmen Cenred and Osric. Cenred

became the new King of Northumbria. He would would only live for two years

before he was succeeded by Osric. Nothing remarkable can be noted about these

two murderous kings and in 729 Osric died and was succeeded King Ceolwulf,

brother of Cenred. Ceolwulf's reign was characterised by his obsessive

religious interests, he was more monk like than king like and was sometimes

ridculed by his people. On one occasion in 732 he was captured and focibly

tonsured - his hair cut in the style of a monk.

From 737 AD to 806 AD Northumbria had ten kings, of which

three were murdered, five were expelled and two retired to become monks. It

brought an instability to the Kingdom which may well have encouraged the first

Viking raiders to attack the Northumbrian coast from 793 AD. King Ceolwulf was

one of the first of these weaker leaders retiring from the kingdom in 737 to

become a monk. He was succeeded by Eadbert, an unremarkable king with an

unremarkable reign. In 750, Eadbert is known to have imprisoned the Bishop of

Lindisfarne at Bamburgh for plotting against him. Eventually, like Ceolwulf,

hewould retire from his kingdom in in 758 to become a monk at York.

Eadbert was succeeded by his son Oswulf, the following year

but Oswulf reign for only a few months before assassination at Corbridge on

Tyne on August 5th 759. He was succeeded by the Deiran, called Athelwald Moll

of Catterick, who may have been responsible for his death. Moll was certainly

capable of cold blooded murder, killing a Bernician noble called Oswin at High

Coniscliffe on the Tees in 761. Moll was not popular with everyone in the north

and was eventually forced out of power on October 30 765 after a meeting was

held at Finchale (near Durham) to decide his future. Moll was succeeded by

Alhred but he too was forced out in less than a decade, by Moll's son Athelred.

And so it goes on, the period seems to be characterised by little more than one

regime ousting another. Athelred was ousted by a Bernician called Alfwold and a

number of royal nobles were murdered at High Coniscliffe during the coup.

In 788 King Alfwold was murdered by his uncle Sicga at

Chesters on Hadrian's Wall and was buried at Hexham. He was succeeded by his

boy nephew Osred II, but the child fled to the Isle of Man to escape his

enemies and Athelred commenced a second period as King. By the end of the

summer 792 Athelred had drowned a rival Prince in Windermere and beheaded Osred

II at Maryport on the Cumbrian when Osred returned to the mainland. He then

attempted to form an alliance with Mercia by marrying the daughter of King Offa

at Catterick.

Perhaps the ruthless Athelred was the strongest in this

sucession of weak kings, but the kingdom of Northumbria was now a shadow of its

former self. It no longer seemed to have the military might of the past and its

religious affairs were in a state of collapse. In 782 and 789 emergency

meetings or synods were held at Aycliffe regarding religious matters and church

discipline. Similar meetings were held at Finchale in 792, 798 and 810. The

inherent weaknesses in Northumbria probably did not escape the attention of

people from far across the North Sea, who soon began to raid the Northumbrian

coast.

VIKING RAIDS

On June 8th 793, in an unprecedented attack which shocked

the whole of Europe, a raiding party of Vikings from Norway attacked

Lindisfarne. Monks fled in fear and many were slaughtered. Bishop Higbald

sought refuge on the mainland and a chronicler would record- "On the 8th

June, the harrying of the heathen miserably destroyed God's church by rapine

and slaughter. " In a letter from Charlemagne's court in France, Alcuin

the former head of York School blamed the Viking attack on a fall in moral

standards in Northumbria. He was well aware of Northumbria's state of disaray

and he for one clearly saw the raid as a punishment from God.

More attacks would follow in 794 with the Vikings attacking

the famous monastery at Jarrow, although on this occasion the Northumbrians

were prepared for the attack and managed to surprise and utterly destroy the

Viking attackers. But further Viking raids on Lindisfarne and Jarrow would

continue throughout the year and by 800 monasteries at Whitby, Hartlepool and

Tynemouth were also targets. The monasteries exposed on the eastern coast of

Northumbria were wealthy treasure houses that were an irresistable target for

the Vikings.

King Athelred's reaction to the Viking raids is not

recorded, but by April 18th 796 he was dead, murdered at Corbridge as the

result of a plot by a Northumbrian noble called Osbald who succeded Athlred as

king for just over a month before he was forced out by a new king called

Eardwulf. Eardwulf was ousted in 806 by Alfwold II, but was restored to power

in 808 following Alfwold's death. Eardwulf was ousted again in 811 and succeeded

by Eanred.

Northumbria was by this time a backwater, no longer a big

player in English affairs. This became blatantly clear in 829 when the most

powerful king in England, Egbert King of Wessex and Mercia called a meeting

with Eanred of Northumbria at Dore near Sheffield on the Northumbria-Mercia

border. Dore was literally Northumbria's 'doorway' to the south.The aim of the

meeting was to ensure peace, and the result was that Eanred was forced to

accept Wessex supremacy and recognise Egbert as the 'overking' of England.

Wessex was now firmly established as the most powerful Anglo-Saxon kingdom in

England and would remain so until 1066.

In Northumbria, King Eanred's reign would outlast many other

kings of this period and he remained in power until his death in 840, when he

was succeded by his son Athelred II. Throughout this period Viking raids

continued to be a problem on the Northumbrian coast. In 830 the monks of

Lindisfarne were forced to flee the island with the coffin of St Cuthbert to

escape further raids. They settled inland at Norham on Tweed where a church was

built for the saint's shrine, but this was only the beginning of a long journey

that would see them travel widely throughout the North.

Vikings raids were by a now problem almost everywhere in the

British Isles. In 841 Vikings from Norway established Dublin as their chief

coastal stronghold in the British Isles and Viking colonies were developing on

the islands off the norther Scotish coast. The first Northumbrian king to fall

victim of the Vikings was Raedwulf, who was killed by Vikings, probably in a

coastal attack in 844 shortly after he had ousted Athelred II from the

Northumbrian throne. The fortunate Athelred was restored and reigned until his

death in 848 when he was succeeded by King Osbert, one of the last AnglIan

kings of Northumbria. In 866 Osbert, the Anglo-Saxon King of Northumbria was

overthrown by his people and replaced by Aelle II. Osbert and Aelle were

perhaps brothers, but they were linked respectively to the Bernician and Deiran

factions of the Northumbrian royal family and their rivalry was one aspect of a

long running civil war.

Holding onto leadership was a major challenge for the

Northumbrian kings in this era, but in 866 an even greater threat to the

stability of leadership was about to emerge. For seven decades the Vikings had

been raiding the coast of Britain and it seemed inevitable that they would

eventually launch a full scale invasion of our shores. This is precisely what

occurred in the year 866, when a huge army of Danes, invaded East Anglia from

their well established bases in the Low Countries of the Continent. They arived

under the leadership of Ivar the Boneless and his brothers, Halfdene and Hubba

and after camping the winter, turned their attention to Northumbria.

Landscape Practitioners

I wanted to look for landscape photographers who captured the northeast like I remember it as a child.

Mark Banks

Joe Cornish

After over thirty years as a working photographer, and

nearly twenty years leading tours and workshops, Joe's love of and enthusiasm

for photography remain undimmed. "Every day out with the camera is a good

day, especially if it involves a spot of walking." Joe says, emphasising

that passion for the landscape is integral to his photography. Supporting

others to improve their photography is also an important part of his life, one

in which he is still constantly learning. Initially a reluctant convert to digital

technology, having been a passionate large format film photographer, he has

learned digital the hard way on medium format backs and through printing, and

has become an enthusiast. "The potential of digital photography is

limitless, but it does require thought, practice, passion and commitment to

make it work for you," he says, "Understanding the links between

fieldwork, light, composition and how that can best be served by suitable

post-production and interpretation is where the process becomes an art."

Joe's own photography has been widely exhibited and he has contributed to large

numbers of books as well as writing land illustrating a number of his own,

including First Light, a landscape photographer's Art, one of the most

influential books of its kind. Joe has been involved in a number of high

profile roles including the Distinction panels of the RPS, the judging team of

Wildlife Photographer of the Year, and as host of the Natural History Museum's

annual Understanding Photography events. However, these do not distract from

his main preference in life, to be outside with his camera, and to encourage

others to do the same.

SMC: Where in the UK do you live?

JC. North Yorkshire, England.

SMC: Age?

JC. 43.

SMC: What is your background?

JC. I’m from the South West of England, born in

Exeter, Devon. I was raised &

educated in Devon and then went to Reading University, where I studied Fine

Art, and it was here that I discovered photography. I had never touched a camera before. After graduating, in which I concentrated on

photography though the Uni didn’t like me doing that, I then worked as an

assistant in Washington DC for two years and then as an assistant in London for

another year.

SMC: What is your current job? Or current jobs?

JC. Well I’m a freelance photographer

concentrating on landscape photography.

Most of which I set myself to do for my own publishing company,

joeGraphic (for details or information on joeGraphic or on Joe's range of

calendars & publications ring 01642 713444 or fax 01642 711177. Have a look at Joe's website -

www.joecornish.com ). But I also do

commissioned work, mainly for the National Trust and other environmental

agencies. That’s the sort of client I

prefer to work for.

SMC: I’ve heard you also run photographic

workshops. What is your main motivation

for doing this?

JC. That’s a very difficult question; it

certainly isn’t money because it isn’t very well paid. I suppose I do it for the sense of

fulfilment. I don’t really regard it as

teaching. I can perhaps point out some

things people might not have noticed and by being there, sharing my vision of

lighting, composition and timing, might help the participants to get a greater

sense of achievement in the work they produce.

That gives me a lot of pleasure!

All images © Joe Cornish 2001

Your Work:

SMC: Lots of people regard you as a master of

landscape photography. Do you feel more

motivated to do more and better or are you scared to be disappointing?

JC. I feel very motivated to do more and better,

I feel very much that the best is yet to come and I don’t think there is any

photograph that I’ve ever done that I would say is on a level with an Ansel

Adams or an Edward Weston. For me they

remain a kind of benchmark that I aspire to.

I would like to take pictures that move people in the way they did, or

make people think about why they live the way they do. There is certainly a long, long way for me to

go. But I’ve never been scared of disappointing.

SMC: Do you think Mother Nature

is fussier, more unpredictable and more versatile than a Top Model?

JC. I’ve never worked with a top model! I know photographers who say top models

always turn up 5 hours late though I’m sure when they do turn up, they are

predictably superb! Mother Nature is a

ferocious God in that she gives with one hand and takes with the other and you

have to learn that you will not often get what you set out for. It’s very often the case that however hard

you plan, you always need to be able to think sideways. The best-planned shot sometimes works as you

had hoped, but when it doesn’t, often a better solution arises behind your back

whilst you are not looking. It’s a very

special kind of relationship. You are

subservient to Mother Nature but at the same time she gives you opportunities

you just can’t predict!

SMC: Because you mainly shoot landscapes, did you

have to learn new virtues: patience? Humility? Or something else?

JC. I’m as impatient as most people are. I’m a driven kind of individual and very

competitive with myself and in my early days I used to get to really get down

on myself when I’d missed something. Over the years I’ve learned that there

will always be something I’ll miss and that I’ll go on missing things. It’s not so much a philosophy of patience but

more a philosophy of acceptance and even of humility! We are very, very insignificant but at the

same time If you bring the right attitude to the situation, your chances of

success are improved. It’s like the old

golfers saying, “the more I practise, the luckier I get”. I think that’s very true in landscape

photography!

SMC: Is your dedication to

“Landscape a way to resist against modernity?

JC. I think that modernity is a word that can be

misinterpreted but if by modernity you mean the industrialisation of

agriculture and by the creeping addiction to comfort and the material world, by

which we are all affected, then yes! It

is an antidote to that. But I also

believe that what is truly modern, is to look into the future and see a way

forward for all humanity. I feel that my work is about that; it is about

reconnecting with nature. I feel strongly that the only future is one in which

we learn to live in some kind of harmonious relationship with the natural world,

because the way we live at the moment is not sustainable for long.

SMC: Along your photographic career, did you go

though different phases, different styles?

JC. I have had to do many different kinds of jobs

over the years. Simply because of the imperative

to make a living! I had very little

money when I lived in London and I did almost everything, anything clients

would give me to do! Many, many boring

jobs but as to whether they changed my style, the answer is no! I think there is a direct link between the

pictures that I did as a degree student and the pictures that I do now. There is the same sense of composition and

lighting that I use today, except then it was all B/W whereas I now work in

colour.

All images © Joe Cornish 2001

SMC: What is the strangest thing you had to shoot?

JC. OK, well it won’t sound very interesting but

you remember the 80’s? When computer

paper had sprocket holes down each side.

One of my clients needed a really gorgeous shot of this paper. I set it up on a huge sheet of black Perspex

as a kind of zigzag line. It was lit in

an interesting way, almost like a landscape if you like! Like a mountain range! That’s the strangest shot I can think of

anyway!

SMC: What changes would you make in your method of

work, if any?

JC. I think the answer to that is that I wish I

could take the unreliability out of film processing! If I could, I would be more secure about the

whole experience with labs, which I find a bit worrying. Shifting no blame onto any particular lab, I

know all labs’ get occasional problems with chemistry. I love film, but there is a hit or miss

element to it’s processing. Not that I

would want to get involved in processing it myself!

SMC: As we said, the category “Landscape” is your

first choice. What would be your second?

JC. Tough question. I also love shooting architecture and

people. But I think I’m not so good at

people! Whereas I’m reasonably good at

architecture, I think it would be a tougher challenge for me to shoot

people. Editors note: Regarding Architecture, Joe chose to show us

his shot of Tomar, Portugal, which

brings him fond memories of that building.

All images © Joe Cornish 2001

Your Gear:

SMC: Your equipment?

JC. I do almost everything on a lightweight 5x4

Ebony view camera. I take as many lenses as I feel I would need on a shoot,

might be two or three, but sometimes five or six, if I feel I need more scope

on a shot Editors note: Joe told us that

on a difficult shoot he might take as many as ten lenses for his 5x4 view

camera but these six are the most used 58mm XL f 5.6, 90mm f 4.5, 120mm f 8,

150mm f 5.6, 210mm f 5.6, and 300mm f 8 (telephoto).

SMC: Black/White or colour? What

do you prefer?

JC. That is an impossible question to

answer! I love B/W, I was brought up

shooting B/W and I feel a deep attachment to the great American photographers

of the Mid-West. But having said that,

since Fuji Velvia appeared in 1989, I believe that this was a significant

development for landscape photography.

This film has such a magnificent emulsion for recording colour

landscapes it’s actually inspired a new wave of colour photography which I

certainly feel part of!

All images © Joe Cornish 2001

SMC: Do you have a digital

camera? Why yes, why not?

JC. I don’t have a digital camera. If I wanted to buy a snap shot camera I would

be perfectly happy with a digital, I have no prejudice against digital

technology it’s a matter of the right tool for the job. After all that’s what a camera is! At the moment I require two things from my

equipment – one is very high quality reproduction and the other is the

flexibility and control of the view camera.

The digital solution means much more weight and a huge investment

because high quality digital backs are so expensive. Also they aren’t actually practical for short

exposures, they require longer scanning times.

So, at present, the technology doesn’t suit my needs!

YOUR PICTURES

SMC: What was your first step in

photography?

JC. I remember my Father had a camera and it used

to take him a year or two to get one film through! He would only take pictures at holiday time. I always wanted to take pictures which was

considered “inappropriate” at my age then.

I never touched a camera until my gap year, before going to

University. My Father actually lent me

his, when I went to New Zealand where I took snaps with it. But photography didn’t really start for me

until I bought an SLR when I was at University.

SMC: What is your favourite

picture? Can you tell us the little

story to go with?

JC. I don’t have a particular

favourite; I’m not very good at making that kind of selection. My pictures represent a particular experience

for me, I have perhaps ten that are my favourites because they are associated

with happy memories.

SMC: Are you the type of

photographer who just takes one shot on a subject?

JC. Simple answer yes, but also no! There are times when I do more. That phrase of Edward Weston, you know, the

“climax of emotion” that’s what I am aiming for. I try to get the best moment at any given

time, the best perspective, the best composition, best timing. So I focus on one thing at a time. I don’t rush around trying to get lots of

shots. I try and make every shot the

best shot I can do. I might take three

or four different shots at a good dawn with two exposures of each. If the light was very difficult I might end

up taking two more at a different exposure.

SMC: Do you like to show your

pictures?

JC. Yes I do, I’m unashamedly proud of my

pictures! I love showing my work and

generally I get good feedback about it.

I think it’s because I feel a passion about the places I shoot, I tend

to go to places I like and that I have a feeling for. It gives me a chance to talk about the place

as much as my work.

SMC: Do you think you have a fair

opinion on others photographer’s work?

JC. I believe I do. I have a great respect for other

photographers and I have been highly influenced by a number of photographers

who have given me guidance, deliberately or otherwise, in the past. I have been inspired by the work of Charlie

Waite, Paul Wakefield and Denis Waugh.

Also the Americans David Muench, and Michael Fatali. However, the one I hold in greatest esteem is

Peter Dombrovskis. And as to whether I

exaggerate the importance of other photographers, as some suggest, I’m not

sure. I’m confident in my own work but I

hope I’m also scrupulously fair about others work. I try never to denigrate another photographer’s

work!

SMC: Do you keep all your

photographs even the junk?

JC. No!

SMC: Your “biggest

disappointment” in photography?

JC. The most recent huge disappointment I’ve had,

is that we had superb snow conditions for landscape photography just a couple

of weeks ago. I’m sure all landscape

photographers reading this will remember!

But because of the Foot & Mouth outbreak and restrictions, I was

unable to go out onto the hills near my home or to go to Scotland where I would

have loved to have been. Obviously my

disappointment is irrelevant compared to the suffering of the farmers but

that’s my example!

SMC: What is your favourite

“ingredient “ for a good photo?

JC. It has to be a lighting thing. If I look at other peoples work there’s a

little thing with me, if I see something about the lighting that moves me or

lifts my spirit then that’s what I go for every time!

SMC: Do you have a secret little trick to make

your photo always so stunning? You can

answer Yes or No!

JC. No because it’s an accumulative thing, a

combination of a huge number of different elements. I am aware of the factors that come into

play, sometimes though things don’t always combine correctly but basically it’s

about space, light and composition. It

is an unpredictable medium and this makes it exciting however many times you go

out. You can accumulate this vast body

of experience in your brain and yet if you follow a formula in landscape

photography, you get found out very quickly.

You constantly have to renew yourself and your creativity.

All images © Joe Cornish 2001

Your Inspiration:

SMC: Are you just suddenly

inspired? Or do you plan a project?

JC. I’m very much a planner though I’m very

inspired by light! If it’s a beautiful

afternoon and I’m working in my office and I see an interesting lighting event

unfolding across the hills, I’ll then stop everything, throw a pack in the car,

walk up the hill and I’ll see what I find.

Even if its just pure sky with a tree silhouetted. But that’s unusual, often I work out in

advance what I want to do. Combinations

of elements and events to do with the seasons, types of weather, still water or

changing leaves, any number of things that you can imagine. I try to catch those things at their most beautiful.

SMC: what are your:

Favourite photographer – Black

& White, Ansel Adams, Colour, Peter Dombrovskis.

Favourite subjects – Coastal

landscapes

All images © Joe Cornish 2001

Favourite spots - Colorado

Plateau

Favourite mood –

Interesting! Light out of darkness. In a way I can transfer that to myself,

having often been despondent because of the weather. And I’m frequently affected by the weather. Then seeing the light changing I find my mood

physically change as well.

SMC: Do you think overexposed

locations have nothing to say anymore, or new talents, new technique can make a

difference?

JC. I

absolutely believe that overexposed locations usually become overexposed

because they are the most graphic and dramatic places. Take Bryce Canyon, Grand Canyon, in fact the

whole Colorado Plateau! I believe there

are always more things to do. The

challenge to the photographer is to go to these places with a completely open

mind and not to feel jaded by the pictures they’ve already seen. It is harder, much harder to go to those

places and be original but that’s what that experience is about, trying to see

it for the first time with fresh eyes.

SMC: Are you perpetually out and about to find new

spots?

JC. No I’m not.

I guess if I were a single guy with no family commitments I think I

would enjoy travelling a lot more than I do.

I’ve come to accept that I’m not single.

My family matter a great deal to me; I would be a remiss Father if I

travelled anymore than I do.

Your view on

SMC: What do you think about Contemporary Art

Photography?

JC. My interest in Contemporary Art photography

waned about seven or eight years ago because I realised that I could never be

part of it. Whether that’s because I’m

too stupid to understand it or because it is a con, I’m not certain! I didn’t see anything that touched me when I

lived in London and I did go and see a lot of Contemporary Art shows. Very little of it affected me on a personal

level. I can only say no, I don’t think

about it.

SMC: What changes has fame made

in your life?

JC. It terms of my daily life it has made no

difference at all. I don’t feel any

different and fortunately, as a photographer, fame is relative! Fame is only the exposure you have to other

photographers and to be appreciated by your contemporaries and your peers gives

real fulfillment. Fortunately it doesn’t

mean having to cope with being recognised all over the place like celebrities

are. I would hate that.

SMC: Can you describe yourself in

3 words?

JC. Persistent, driven, hopeful.

SMC: What would be your advice to a beginner in

photography?

JC. Don’t do it for the money! Only be a photographer if you feel passionate

about it. That’s especially true for

landscape photography. If you are

passionate about it then you will have the drive to take you through the

inevitable disappointments.

Your dream

SMC: What is your dream as a

photographer?

JC. My dream is to be able to make a

difference. You can interpret that in anyway

you like. I try to connect with the

landscape but on a personal level and by doing so I try to express my own

spiritual connection or experience of it.

If I can do that and move others in that way, if it makes a difference

to them then that’s my dream I guess.

Charlie Waite

Charlie Waite is an English landscape photographer, noted for his “painterly” approach in using light and shade.

Charlie Waite is an English landscape photographer, noted for his “painterly” approach in using light and shade.

Faye Godwin

Faye Goodwin was a British photographer known for her black-and-white landscapes of the British countryside and coast.

Hyperfocal distance focusing The traditional way of using it is to focus on the subject and then use the lens’ depth of field scale (or a tape measure and depth of field tables) to find out where the nearest acceptably sharp point is.

This point, where the depth of field starts in front of the focus point, is known as the hyperfocal point.

Alternatively, you can rely on the principle that depth of field extends roughly twice as far behind the point of focus as it does in front and focus approximately one third of the way into the scene.

Hyperfocal distance focusing is popular in landscape photography and whenever you need lots of depth of field.

Faye Goodwin was a British photographer known for her black-and-white landscapes of the British countryside and coast.

Professional Practice and Technique for Landscape Photography

This is a popular camera focusing technique that is designed to get the maximum amount of a scene sharp at any given aperture.

Once the hyperfocal point is found/calculated, the lens is refocused to it so that the subject remains sharp and greater use is made of the depth of field

The popularity of zoom lenses and consequent loss of depth of field scales has made it harder to apply this technique precisely, but you can still measure or estimate the focus distance and use smartphone apps such as DOF Master to tell you the hyperfocal distance.

Focus stacking

This is a digital technique in which several images taken with different focus distances are combined into one image that is sharp from the foreground all the way through the background.

Although it can be applied to landscape photography, it is especially useful for macro photography because depth of field is very limited when subjects are extremely close.

With the camera firmly mounted on a tripod, take the first shot with the nearest part of the scene in focus. Then, without moving the camera, refocus just a little further into the scene and take the second shot before focusing further in again.

Repeat this until you have a shot with the focus on the furthest part of the scene.

Now all the shots can be combined to create one image that is sharp throughout. This can be done manually using any image editing software that supports layers – Photoshop Elements is fine.

But it can also be done automatically using software like Combine ZM, which is free to download and use, or using Photoshop’s Photo Merge function.

Tent

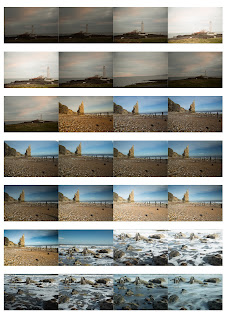

The light on the beach made this shot interesting as the sun rose in the sky. I had to use a polorisor to deter reflections and flare in the lens alongside a soft graduated filter to bring down the light in the sky. The polorisor helped to keep the colour of the rising sun in what was quite harsh lighting conditions.Stacked from two exposures to create the light in the sky and the light on the beach, blended using photoshop.

Tripod Used

iso 100

32mm

F13

1/30sec and 1/100th second

Edit Photoshop

Taken before sunrise and photostacked using 6 images. I wanted to capture the light on teh rocks and emphasise the colours it was creating. I stacked the images to capture the light and textures and blended them in photoshop.

I decided to make a book about The Bernica Project using the images I took but also adding a little historical content about the places I visited to give the book a more educational feel.

Landscape Photography Guide

I have been planning to write this landscape photography guide for a long time, but held it off for a while, thinking that I could do a better job after learning about it more. My landscape photography journey has been a big learning curve and I have been enhancing my skills so much during the last few years, I realized that I could spend the rest of my life learning. Therefore, I decided to write what I know today and keep on enhancing this guide in the future with new techniques and tips.

1) Preface